I had my first Natural Dyeing class at the Oregon College of Art and Craft last week. We started by walking the campus and collecting various autumn flora: fallen oak and maple leaves, pink-backed cherry leaves, fresh comfrey, spotted dying blackberry leaves, walnut hulls, tupelo, madrone and walnut leaves, Indian blood grass, and anything else that caught our eye. The ostensible purpose of this was to collect material to make our own contact dyed projects, but really it was to get us excited about natural dyeing. This time of year in the Pacific Northwest the ground is littered with dyestuffs, and the quick and easy method we learned yielded pattern as well as color.

Once we collected our leaves, we laid them out onto fabric or paper, and either rolled up our fabric tightly around a stick (or for added color, around a rusty iron nail) or accordion folded and clamped for a shibori effect. These packets are then simmered in a water bath for an hour, and then removed and unwrapped.

What I found most interesting about this technique is that there is really very little dye in individual leaves (for the most part tannic acids) but because of the wrapping or clamping, the color can’t migrate anywhere other than onto the fabric or paper. In other words, the opposite of leveling. In a lot of cases, the color transfer is more akin to printing— the fabric or paper is not really dyed per se, but stained or imprinted with the actual leaf color, giving pinks or greens which don’t exist as an actual dye. Our instructor cautioned us as much, saying that these colors will fade with washing or over time. That said, there definitely was dyeing of fabric around the periphery from the tannic acids, and also where the rusty nails provided an iron mordant.

Here is a leaf print where I had an iron plate clamped to the outside of my fabric packet:

And likewise wrapped around a large rusty nail:

Here is the difference of the dyestuffs on cellulose. For one, I didn’t get my packet wrapped tightly enough and the colors ran. For another, the yellows and greens remained printed while the tans of the tannic acids didn’t penetrate as much. I expect this to be a function of the density of the cellulose in paper form, and I would expect better tans on cotton yarn:

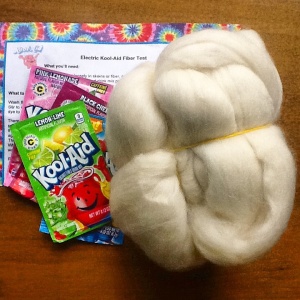

This technique also led me to revisit my forays into dyeing with candy. I’d encountered poor results with a lot of candies that contained very little dye. So I tried some candy contact dyeing:

The candy melted pretty quickly, so it was hard to keep the fabric tight, but the dye migrated onto the fabric rather than into the dye pot. I can see some candy-related shibori in my future!

I’d also encountered some inexpensive pomegranates at the grocery store last week, and per Rachel’s last post I bought them for some seasonal dyeing. Pomegranates contain ellegic acid, which are yellow tannins, so I thought this would be a quick way to see what sort of coloring I could get from them:

This is one slice of pomegranate:

And here is multiple slices and layers, with the rest of the pomegranate in the dye pot:

Tight wrapping and clamping is the key to good transfer, but whether you are preserving autumn leaves, testing dyestuff potential, or finding another use for seasonal candy, it’s such a quick and easy technique that it’s definitely worth trying.